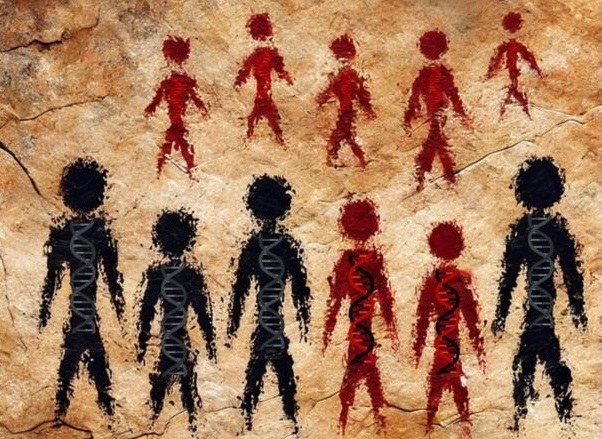

Recent findings by an international team of scientists clarify when modern humans (Homo sapiens) interbred with Neanderthals, as well as the significance of these interactions for the evolution of our species. The research, published in Science journal and other sources, provides not only precise dates, but also detailed information about the impact of Neanderthal heritage on human adaptation to new environments.

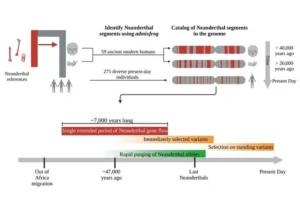

New timeline for species interbreeding

According to genetic analyses, Homo sapiens and Neanderthals interbred about 50,500 years ago, and this process continued for nearly 7,000 years. However, recent studies suggest that in some cases the process may have started as early as 47,000 years ago. Analyses of the genomes of ancient humans, including 59 individuals who lived from 2,000 to 45,000 years ago, indicate that early populations of Homo sapiens may have had as much as 5% Neanderthal DNA as a result of these interactions. Modern humans of non-African descent have an average of 1% to 2% of such genes.

Neanderthal DNA influenced the development of traits related to immunity, metabolism and skin pigmentation, which likely helped Homo sapiens adapt to life in colder regions of Eurasia. These genes were beneficial in the new environments and promoted survival. At the same time, there are areas in the human genome completely devoid of Neanderthal influence – natural selection may have eliminated genes that negatively affected health or reproductive ability.

Genetic interactions occurred mainly in the West Asian region, where migrating Homo sapiens encountered Neanderthals. Interestingly, studies suggest that gene transfer was mainly one-way – from Neanderthals to Homo sapiens. Some of these genes, although common in the past, disappeared in the following millennia, further highlighting the evolutionary dynamics of modern humans.

Archaeology and genetics in harmony

Dates established through genetic analysis correspond with archaeological evidence indicating the coexistence of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals in Europe and Asia. Finds from sites such as Oase, Ust’-Ishim and Bacho Kiro show a large Neanderthal legacy in the genome of the first representatives of Homo sapiens, who died out around 40,000 years ago.

The researchers emphasize that further studies of the genomes of ancient populations, especially from Southeast Asia and Oceania, could provide even more accurate information about the migrations of modern humans and their interactions with Neanderthals. Understanding the Neanderthal legacy may also clarify mechanisms of human adaptation to new environments and challenges.

Sources: archaeologymag.com, www.livescience.com, scitechdaily.com,